When you think of marble statues, what comes to mind? You most likely imagine sculptures of freestanding figures, like the Venus de Milo and David. In addition to these decorative works of art, however, some marble creations are functional, like the ancient caryatid.

Part figurative female sculpture and part architectural element, the caryatid has helped creatively carry the weight of buildings for thousands of years. While they proved particularly popular in Ancient Greece—their place of origin—they continue to blur the line between art and architecture today.

What is a Caryatid?

A caryatid is a sculpted female figure that also serves as a pillar, column, or other supportive architectural element. A traditional caryatid has a capital (the top of a column) on her head, though some also appear to be holding up the entablature (the decorated area above a column) with their arms.

The name “caryatid” is derived from the Greek word, karyatides, which translates to “maidens of Karyai.” Karyai, an ancient Peloponnesian town, featured a temple devoted to Artemis Karyatis, an epithet of the well-known goddess Artemis. To honor Artemis Karyatis, Peloponnesian women would often perform folk dances with baskets of plants on their heads—an image that inspired the aesthetic of the caryatid.

“As Karyatis,” C. Kerényi, a mythologist, explains, “[Artemis] rejoiced in the dances of the nut-tree village of Karyai, those Karyatides, who in their ecstatic round-dance carried on their heads baskets of live reeds, as if they were dancing plants.”

The History of Caryatids

While their namesake is rooted in Karyai, the earliest known caryatids existed in Delphi and date back to the 6th century BCE. Here, caryatids were incorporated into the architecture of buildings intended to house offerings, like the Siphnian Treasury. At this site, the people of Delphi brought gifts to Apollo, an important Olympian deity in both Greek and Roman mythology.

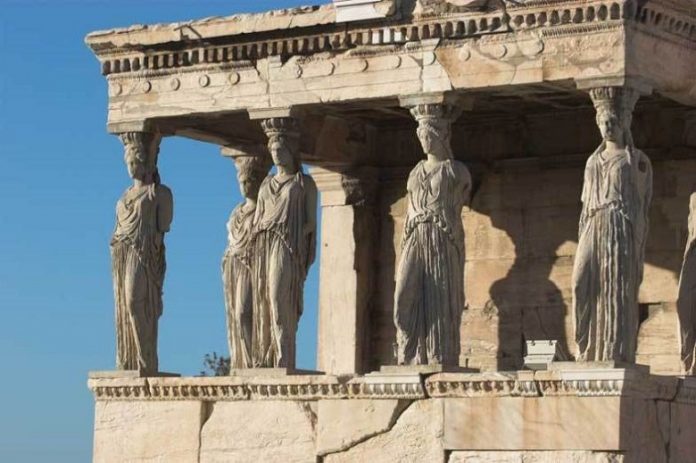

Two centuries later, history’s most famous caryatids were erected in nearby Athens. A group of six, these sculptures supported the false south porch of the Erechtheion, a temple on the Acropolis. While these figures closely resemble one another, they display different stances and feature unique hairstyles, drapery, and faces. Today, replicas stand in their place; five of the original sculptures are in the Acropolis Museum and one is in the British Museum.

Like other Classical art, caryatids fell out of fashion in the Middle Ages. However, during the Italian Renaissance—an enlightened age sparked by a renewed cultural interest in classical antiquity—artists revived the practice. Rather than carve caryatids for use on building façades, however, sculptors began incorporating them into interiors. Specifically, caryatids—and their male counterparts, atlases—were used to support mantelpieces, like that of the famous fireplace in the Sala della Jole, a 15th-century room in the Doge’s Palace in Venice.

For centuries after, artists have been inspired by Renaissance figures and they began creating their own caryatid adaptations. Mannerists employed caryatids as a means to experiment with and emphasize drapery; English woodworkers crafted exquisite caryatids for elegant Jacobean interiors; and, in America, 19th-century architects added caryatids to museums in a nod to the institution’s classical roots.

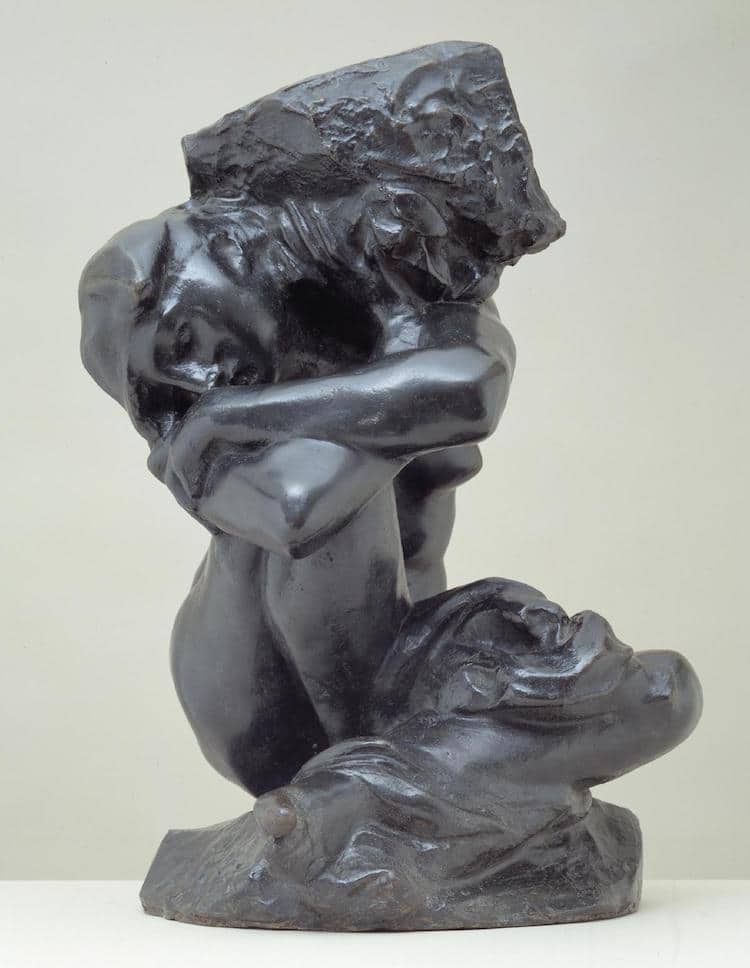

Even prominent modern artists have employed the caryatid motif in their work. In the 1880s, French sculptor Auguste Rodin, for example, sculpted Fallen Caryatid Carrying her Stone for The Gates of Hell, a colossal double door sculpture portraying a narrative from Dante’s Inferno. Like many of the figures featured on this work, Fallen Caryatid Carrying her Stone went through a stylistic evolution throughout the piece’s 37-year design and construction. “The Fallen Caryatid first appeared as a small, crouching woman at the top of the left pilaster of The Gates,” the Metropolitan Museum of Art explains. “About 1881 Rodin enlarged the figure and added a stone.”

While neither the largest nor the most prominently placed character on The Gates of Hell, The Fallen Caryatid Carrying her Stone is one of its most celebrated. “This supple little creature,” a critic wrote in 1889, “not more that eighteen inches high, is regarded by the sculptor and his friends as one of his very best compositions, and many copies of it have been made for the latter in both marble and bronze.”

Though undoubtedly attributed to Rodin’s expert craftsmanship and modern design, this analysis also speaks to the lasting legacy of the caryatid, a sculptural tradition that has survived thousands of years and continues to captivate with its innovative versatility.

By Kelly Richman-Abdou

Source: mymodernmet.com