The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) comes into force at the end of this month. The deal creates one of the world’s largest free-trade areas by slashing tariffs across a $2.5trn market of 1.2 billion people.

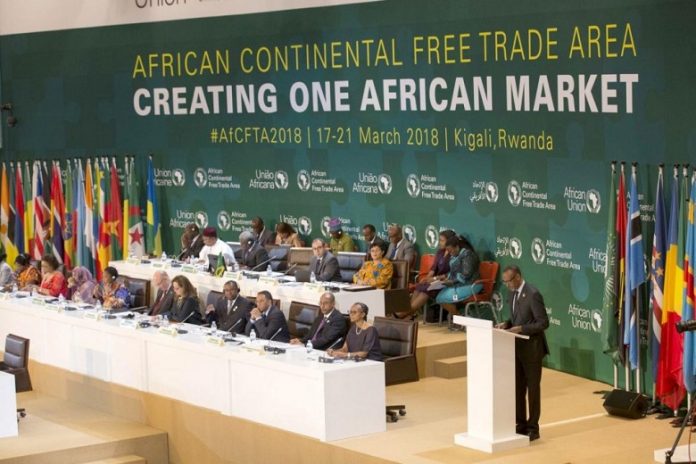

Fifty-two African states are now committed to cutting duties on 90% of goods and 27 countries have signed a protocol providing for freedom of movement. Rwandan president Paul Kagame hailed the deal as a “new chapter in African unity”. The accord bucks a global trend as populism and trade wars on other continents set globalisation into reverse.

Poor infrastructure, elaborate customs procedures and high tariffs – currently averaging 6.1% – have long hampered the development of intra-African trade. The Gambia, for example, currently exports more to South Korea and the Netherlands than it does to neighbouring Senegal.All told, trade between African states accounts for just 15% of the continent’s trade. In the EU the equivalent figure is 67%.

The intention is for AfCFTA to be a stepping-stone to more comprehensive pan-African integration, with a customs union in the pipeline. The more distant dream is to create a frictionless single market allowing a South African factory to import parts from Niger to make into a product to be sold in Egypt, says Tom Rees in The Daily Telegraph.

AfCFTA is certainly ambitious, says Vera Songwe for the Brookings Institution think tank. It extends beyond goods – the stuff of a traditional free-trade deal – to include services, investment, intellectual property and possibly e-commerce.

The biggest problem is that Nigeria, the continent’s biggest economy and most populous nation, has yet to sign. The country’s manufacturing interests have been lobbying hard for special protections, citing fears of “dumping” by more competitive foreign industries. With more than 190 million people, Nigeria’s large internal market means that its leaders feel a less pressing need than smaller neighbours to secure access to a wider African market.

Even if Nigeria does eventually get on board, planned negotiations on competition rules, investment and intellectual property rights will provide plenty of opportunity for more fireworks between the continent’s protectionist powers and more liberally inclined governments in countries such as Ethiopia, Rwanda and Ghana.

The UN forecasts that if Nigeria joins the AfCFTA then intra-African trade could grow by more than 50% in the next five years as the continent taps into latent economies of scale. Yet even without a trade deal, much has gone right in Africa in recent years. GDP per head south of the Sahara is up 40% since the year 2000, notes The Economist.

The biggest drag comes from relatively weak performance in recent years by the “big two” of Nigeria and South Africa, but the IMF forecasts that sub-Saharan growth will hit 3.5% this year, with notable strength from east African states such as Ethiopia and Rwanda.

The EU remains the continent’s largest trading partner for now, with $156bn worth of trade last year, but China is not far behind on $120bn.

Source: moneyweek.com