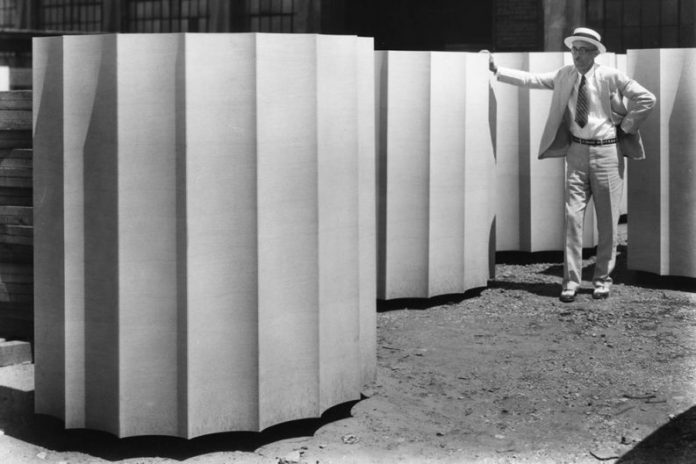

Stone from Knoxville-area quarries adorns some of the most famous buildings in America.

Geologists note that Tennessee marble, often pinkish in hue, is actually a crystalline limestone. However, it has been known as “Tennessee marble” for two centuries.

Knoxvi l le marble is obvious in the architecture of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., claimed to be the largest marble building in the world.

Other buildings that feature Knoxville marble include New York’s state capitol, the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, New York’s Grand Central Station, and the New York Public Library’s famous stone lions, Patience and Fortitude.

***

Knoxville has hosted several marble producers, including the Tennessee Marble Co., on Riverside Drive, the Ross-Republic Marble Company near Island Home, the Candoro Marble Works in Vestal, the Appalachian Marble Companyon Middlebrook Pike, and the Gray Knox Marble Company on Sutherland Avenue.

***

Ramsey House, built in 1797 on Thorngrove Pike in East Knox County, near traditional marble quarrying sites, is one of the earliest known Tennessee marble structures.

Knoxville began producing marble for commercial use by 1852, when James Stone opened a quarry two miles north of downtown to supply stone for Nashville’s new state capitol building. The arrival of railroads in 1855 made marble-quarrying a major local industry.

The Ross and Mead families operated quarries on the south side of the river near Island Home, on what later became known as Ijams Nature Center. The oldest dates to the 1880s and, largely reclaimed by nature, resembles a small wooded canyon.

***

“The Marble City” was a term often applied to Knoxville beginning by the 1880s. Multiple downtown businesses used that name, including the Marble City Bank and the Marble City Saloon. After 1910, a specific neighborhood along Sutherland Avenue became known as “Marble City,” reflecting the marble workers who lived there, near more than one marble company. The city as a whole was sometimes referred to as “the Marble City” as late as the 1950s. Marble has played an important role in Knoxville’s cultural history. Knoxville’s first professional artist, Lloyd Branson, was best known for a 1910 painting of men and oxen hauling marble, called “The Toilers.”

Pul itzer Pr izewinning invest igative reporter Paul Y. Anderson (1893-1938) grew up in a South Knoxville marble family. After his father was quarry accident, Paul’s youth was diff icult, which may explain his tough fearlessness as a journalist. He’s buried under an elaborate marble marker at Island Home Baptist Church.

Designed by architect Charles Barber in 1923, the colorfully unusual Candoro building in Vestal was built to highlight the marble varieties produced by the company.

Albert Milani (1892-1977), who grew up near the famous Carerra marble quarries in Italy, was one of several Italian stonecutters who moved to Knoxville to work for Knoxville’s marble industry. Milani’s work can be seen on the 1912 Holston Building on Gay and especially on the 1934 Post Office building on Main. He was also an accomplished sculptor.

Source: www.knoxmercury.com