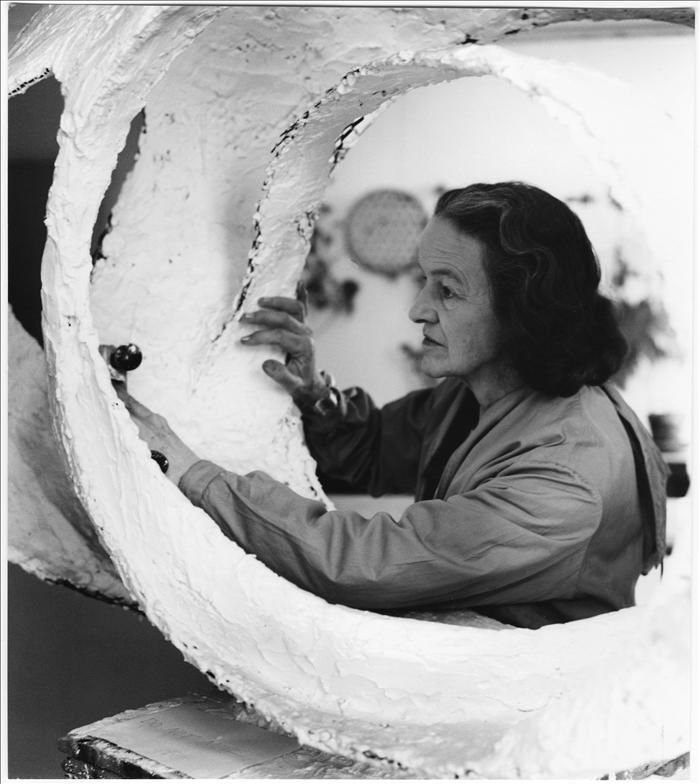

British artist Barbara Hepworth (10 January 1903 – 20 May 1975) was a world-renowned sculptor known for her lyrical, abstract forms. She was fascinated by shape and texture from an early age and decided, at just 15 years old, to become an artist. Her passion made her prolific; during her 50+ year career, she produced an estimated 600 sculptures handcrafted from wood, marble, bronze, and more.

For Hepworth, sculpture could embody life itself. “Sculpture is a three-dimensional projection of primitive feeling,” she once remarked. “Touch, texture, size and scale, hardness and warmth, evocation and compulsion to move, live, and love.”

Hepworth’s Childhood and Education

Hepworth’s Childhood and Education

Born on January 10, 1903, in Wakefield, West Yorkshire, Hepworth was the eldest child of Gertrude and Herbert Hepworth. Her father was a civil engineer, and she frequently accompanied him on trips throughout rural England. These experiences—along with spending her summer holidays at Robin Hood’s Bay in Yorkshire—helped shape Hepworth’s love of nature that later influenced much of her work.

After graduating from high school, young Hepworth expressed an interest in Egyptian sculpture and won a scholarship to the Leeds School of Art in 1920. While studying there, she met fellow student and sculptor Henry Moore. They became life-long friends and influenced each other’s work throughout the rest of their careers. They both went on to attend London’s Royal College of Art in 1921. Hepworth graduated with a diploma in 1923 but stayed an extra year in order to compete for the Prix de Rome, a French scholarship for art students to study in Rome. She lost to fellow sculptor John Skeaping, who later became her husband.

Early Career

Early Career

Hepworth married Skeaping in May 1925. The couple moved to Rome where Hepworth first learned to carve with stone under the guidance of sculptor Giovanni Ardini.

In November 1926, the newlyweds returned to London. During this time, Hepworth began to work and exhibit her sculpture at her own studio, where she directly carved into stone using a hammer and chisel. This “direct carving” technique allowed Hepworth’s raw materials to retain an organic quality and deliberately allowed viewers to see the artist’s hand or “signature.”

Hepworth gave birth to her first child, Paul Skeaping, on August 3, 1929. Many of her early works took the form of an infant, or a child and a mother. These figures remained key motifs in Hepworth’s work but were later abstracted. Nature also remained a prominent theme in her work, especially the sea and waves.

Mature Period

Mature Period

In 1931, Hepworth separated from Skeaping. In the same year, she met abstract painter Ben Nicholson, and the pair formed a relationship. (They later married in 1938.) Hepworth and Nicholson lived in Hampstead, in north London, near Henry Moore and several other great artists of the time. Art historian of a friend of Hepworth, Herbert Read, described the area as “a nest of gentle artists.”

During this time, Nicholson and Hepworth shared a studio and often collaborated. Hepworth said of their relationship, “as painter and sculptor each was the other’s best critic.” Hepworth was influenced by Nicholson’s abstract forms in his paintings, so her work became increasingly abstracted, too.

In 1932, Hepworth “pierced” a sculpture for the first time. The work, titled Pierced Form, was made from pink alabaster and featured a smooth, waving surface. The hole in the center allowed the viewer to see right through it. Pierced Form was destroyed during World War II, but Hepworth continued to make sculptures with similar gaping openings. However, Hepworth didn’t see her as holes as gaps, but rather connections between form and space. In some works, she further accented and defined the sculptural voids by stretching strings across their openings, creating works resembling string instruments.

In 1934, Hepworth gave birth to triplets: Simon, Rachel, and Sarah Hepworth-Nicholson. Hepworth recalled, “It was a tremendously exciting event. We were only prepared for one child and the arrival of three babies by six o’clock in the morning meant considerable improvisation for the first few days.”

Between 1933 and 1934, Hepworth and Nicholson took part in the Paris-based exhibiting group, Abstraction-Creation. They connected with iconic abstract artists of the time, including Pablo Picasso, Wassily Kandinsky, Joan Miró, and Piet Mondrian. Hepworth began exhibiting alongside these abstract artists in both the UK and in Paris. In 1936, The Museum of Modern Art purchased its first Hepworth sculpture.

As World War II broke out in 1939, Hepworth and her family relocated to St Ives in Cornwall, England. They stayed there until the war ended inside a small cottage. The cramped conditions meant that Hepworth didn’t have the space to sculpt, so her practice shifted to drawing. She created a series, titled Hospital Drawings (1947–49), which features men and women performing surgical procedures.

In 1949, Hepworth bought a house and studio in St Ives; she would live there for the rest of her life.

Final Years

Final Years

Hepworth’s and Nicholson’s marriage ended in 1951, and tragically, her first son died in a plane crash in 1953. While dealing with the grief, Hepworth continued to sculpt, but she was also battling her own health issues. She was diagnosed with tongue cancer and suffered from mobility problems, but that didn’t stop her from keeping up with the demand for her work. In 1956, she began to work in bronze and other metals which allowed her to create sculptures in small editions.

“Hepworth was small and intense in appearance, deeply reserved in character,” wrote Sir Alan Bowness, Hepworth’s son-in-law, and an art historian. “It was always surprising that an apparently frail woman could undertake such demanding physical work but she had great toughness and integrity.”

In 1975, Hepworth fell asleep while smoking a cigarette at her studio in St Ives. The building burned down, and Hepworth died inside. Her obituary in The Guardian described her as, “probably the most significant woman artist in the history of art to this day.”

Source: mymodernmet.com