Hoisting 20,000 pounds of marble (twice the weight of a killer whale) into a sixth-floor Manhattan loft is no easy feat. But artist Hanna Eshel didn’t shy away from Herculean challenges, especially when it came to making art. In 1978, then in her early 50s, Eshel moved from Carrara, Italy, to New York City with stone slabs and sculptures as her companions; she lifted them by crane into her new downtown home. “Could transporting mountains of marble sculptures from Carrara to N.Y. make me an AMAZON?,” she wondered, in a 1983 statement, drawing a tentative comparison between herself and Greek mythology’s famed female warriors.

By the time Eshel settled into her New York apartment in the late 1970s, she’d already proven herself to be something of a fighter—one who persisted in making art the center of her life despite a long run of hurdles. This month, an exhibition at New York’s Patrick Parrish Gallery traces the 93-year-old artist’s vast output, which was only rediscovered in 2012, intact and strewn intentionally across her longtime NoHo loft. Embedded in a maze of house plants, rock gardens, and books on art and spirituality were marble sculptures marked with deep fissures, collages striped with chasms, and canvases that erupted with bursts of paint recalling female anatomy, deep-space explosions, and her own tenacity.

By 1952, Eshel landed in Paris, studying painting and fresco at the Acadéemie de la Grande Chaumière and the École des Beaux-Arts. Her canvases veered from two to three dimensions; she layered ruptured burlap substrates with frays. Hot flares of red and orange paint surged from raw, oblong tears. “My burlap-collage paintings were vibrating with fissures, images of my life and time,” she continued in “Life Sketch.” Galleries and museums across the city took note, and Eshel’s work hung on the walls of Galerie Katia Granoff in 1954, Musee d’Art Moderne in 1960, and in solo shows at Galerie de Beaune in 1966 and 1967, among others.

She also married and gave birth to a son. The balancing act wasn’t easy, and, according to Eshel’s longtime friend Quinn Luke, her husband preferred that she focus on her role as wife and mother. “I was now MADAM—a wife and mother, student and exhibiting painter—everything and not enough of anything!” she wrote. The rips in her canvases seemed to presage the divorce she requested, the moment her son went to college in the early 1970s. For Eshel, fissures represented not fragility, but strength and liberation. “I regained my freedom,” she remembered, “divorce made me a full-fledged ARTIST!”

That year, Eshel broke free from both marriage and painting. She’d planned on relocating to New York, but a temporary stopover in Carrara Italy—“to follow in Michelangelo’s footsteps”—turned into a six-year stay. There, she found marble, the medium that would occupy her for over 20 years. “I needed a material with its own soul, one that I could love,” she wrote in her memoir, Michelangelo and Me: Six Years in My Carrara Haven (1995).

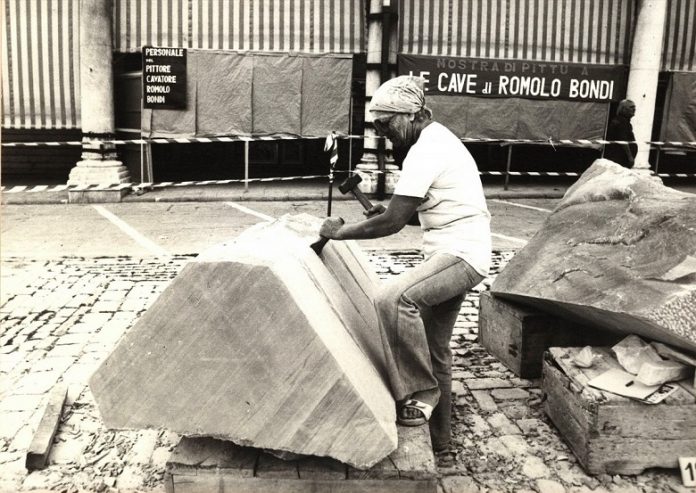

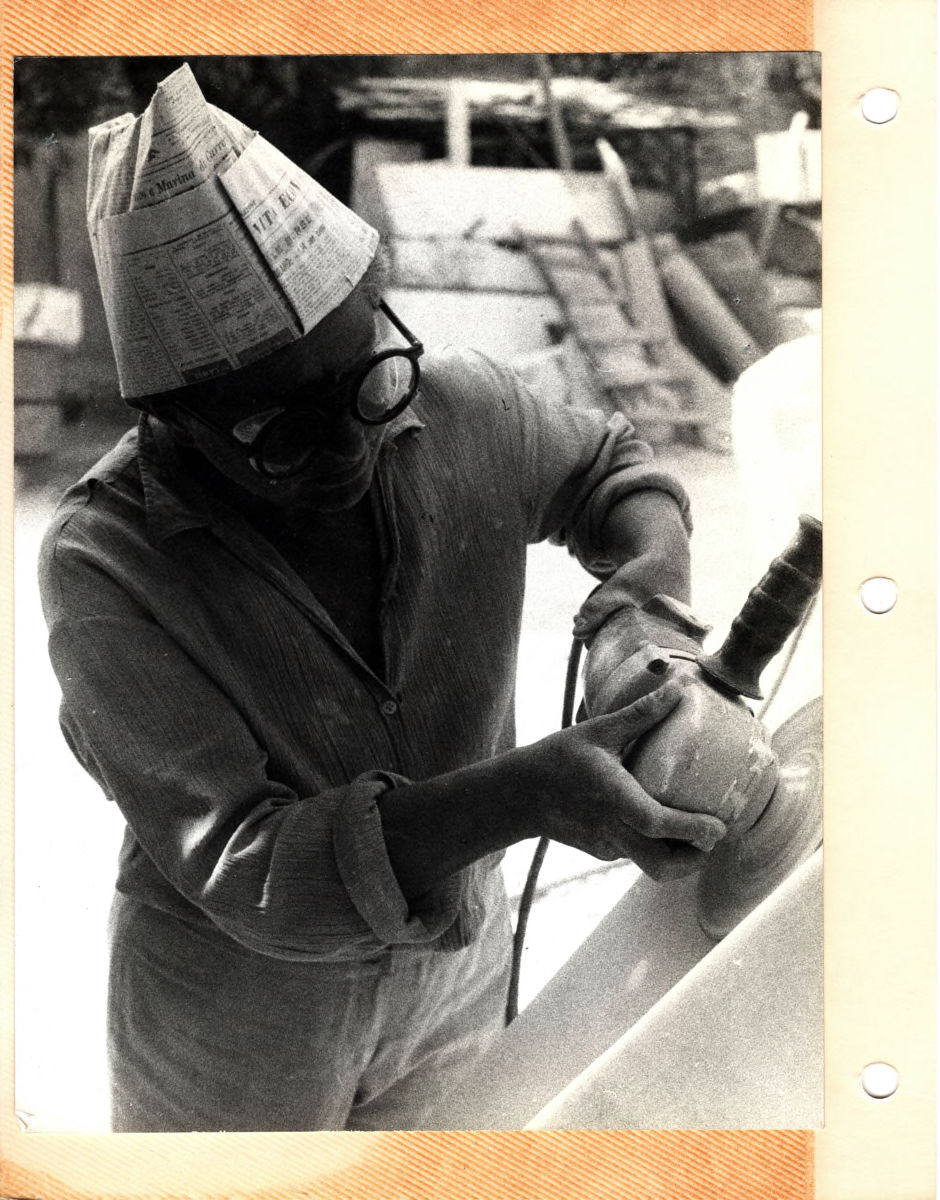

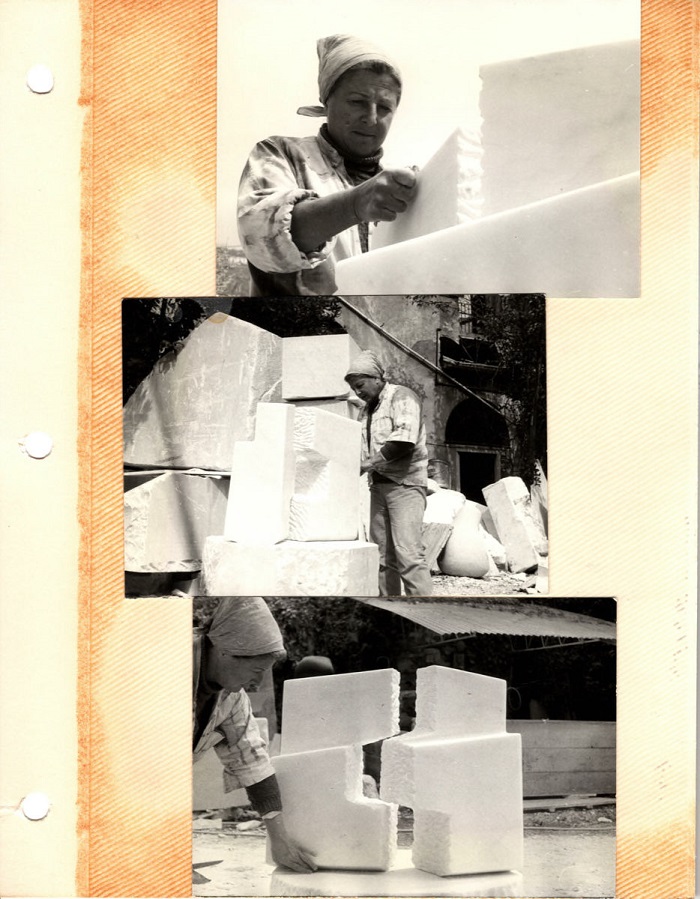

Images from her scrapbook show Eshel smiling in big sunglasses, with patterned bandanas wrapping her head,as she chisels away at gargantuan chunks of stone in open-air Italian studios and town squares. She gouged indentations, crevasses, and deep, wide cracks, resembling lightning bolts into marble. She polished some surfaces to a sun-reflecting sheen, and left others raw and pocked. Photos of lively openings and parties from her stay show her draped in necklaces forged from smaller bits of marble—little buffed ovals resting on her bare clavicle, not too far from her heart.

In “Life Sketch,” Eshel recalled, “I became a SCULPTOR – Brancusi was my artistic father.” She also became the only female member of a group of artists surrounding the Carrara sculpture studio Atelier Nicoli. There, she met Isamu Noguchi and Henry Moore and received the Fiori Carrara prize.

The recognition didn’t follow Eshel to New York. By 1978, when she decided it was finally time to try life in Manhattan, Minimalism had been overshadowed by Warholian Pop and its Neo-Expressionist scions. She had little desire to rub elbows with the growing band of art stars or follow trends that led her away from marble and her sensual, solid, pared-down forms. “I had no interest in promoting art,” she recalled in a 2014 interview with the New York Times. “There was Pop Art and Op Art. I didn’t follow the fashions.” Even so, she found a supportive community of artists (in her scrapbook, they show up smiling and draped over each other at Eshel’s frequent studio parties). Eshel participated in shows at numerous galleries like Art Space, 14 Sculptors, and A.I.R, the renowned feminist art co-op. “I am now MS. ESHEL,” she wrote in ’83, “a very much alive artist, Painter and Sculptor, also a Photographer, showing internationally and making monuments wherever commissioned.”

For the next twenty-some years, Eshel continued to hone marble slabs in her NoHo loft, which gradually became filled with spherical and totemic forms. Some works dotted the sand-lined rock garden she thoughtfully tended to at the center of the sprawling space. “I feel Zen along the sand waves in my garden of marble sculptures,” she continued, “criss-crossed by creating fissures in my work, along my Tao!”

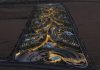

Eshel left New York regularly for long art-making sejours in Carrara, supporting the trips by subletting her rent-controlled loft oasis.She took a camera with her, shooting her beloved quarries and the undulating, craggy rock formations. These images became fodder for collages when sculpture became too physically exhausting for the artist in the early 2000s. The collages, too, lined Eshel’s loft, along with reference imagery. In a 2007 video, a camera pans across photos of parrots, a gaseous planetary orb, and a painting striated with bands of deep umber, yellow, and green. They flutter above a bookshelf topped with bits of grooved coral, carved marble, lush ferns, and an arrangement of dried flowers cradled in the hollow of a bone.

In 2012, when she was in her late-80s, Eshel posted an ad on Craigslist for a roommate. (Over the years, subletting the lofted bed in one corner of her apartment had become a means of supporting herself.) Serendipitously, Quinn Luke, an art advisor, answered. “It felt like you were walking into a space that was curated and operated by the Dia Foundation,” he recalled of his first glimpse of the loft. They became roommates and friends. Luke also became Eshel’s natural advocate, introducing her body of work, which still lived and grew in her studio, to New York galleries. Her last show solo show had been mounted in 1987. In 2013 and 2014, she had her first three exhibitions—at Patrick Parrish (then Mondo Cane), Todd Merrill, and Glenn Horowitz—in almost 30 years.

Eshel and Luke moved out of the loft in 2015, when Eshel became too ill to stay. But she continues to dabble with new materials and live, in her new home in the Bronx, surrounded by her paintings, collages, and sculptures—her self-described anchors. “I still own no house or country home, no diamonds, furs or cars—I am weightless,” she wrote towards the end of “Life Sketch.” Reading this line, it’s hard not to imagine Eshel’s slabs of marble, proxies for her strength and resilience, floating through the window of her New York loft. “But my marble keeps me anchored!,” she continued. “WHAT’S IN A NAME, ANYHOW? It is my art that is!”.

Alexxa Gotthardt

Source: www.artsy.net